Matching problems with the right expertise within and across firms is essential for the functioning of the economy. When problems are complex, however, their owners are often unaware of their exact nature, and costly diagnosis by an expert is required. This is why the initial allocation of problems is often independent of an expert’s specialization, but is affected by publicly available information of the expert’s past success rate in solving problems. Prospective clients, for example, consult medical providers with higher satisfaction scores or lawyers with better track records, while firms allocate problems to managers who got the job done in the past. The services of experts in these scenarios can be described as reputation goods. Reputation goods are (1) differentiated between sellers, (2) their product quality is consumer specific (3) and initially uncertain, (4) important, and thus (5) worth considerable information acquisition effort. In order to strengthen their reputation, thereby increasing demand for their services, experts sometimes find it worthwhile to forego compensation and sometimes refer problems to other experts who may be a better fit.

In Strategic Referrals among Experts (joint with Yi Chen and Mark Satterthwaite), we build a dynamic model to examine how reputational concerns of specialized experts shape their referral behavior and, as a consequence, market outcomes. We find that competition for problems among individual experts does in general not result in an efficient allocation of problems across experts. What is more, instead of sharpening their expertise, experts may want to invest in their abilities outside of their specialty—to the detriment of the economy. This issue may be exacerbated by the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the workplace, often increasing professionals’ productivity outside their main specialty. Also, market efficiency increases in the experts’ compensation for diagnosing problems relative to treatment, potentially discouraging them from specializing in the first place. We show that referral alliances that set referral prices may alleviate these issues, though possibly at the expense of some experts. Pareto-efficient market outcomes generally require revenue sharing beyond referrals, i.e., some form of partnership contract. It is therefore imperative to account for referral incentives when regulating markets for professionals.

Our model features an economy with a mass of experts of two different types, who compete against each other for problems in continuous time. Each problem belongs to one of two categories, matching the experts’ types. That is to say, an expert has an absolute advantage (higher success rate) in treating problems of their category, i.e., those that match their type. Since problems require costly diagnosis, the demand for an expert’s services, i.e., the problems they receive, is independent of the expert’s type. An expert initially diagnoses problems, and then, for each problem, decides whether to to treat it or refer it to a more apt expert.

The demand for an expert’s services at any point in time depends on their own and other experts’ record of solving problems. An expert can solve a problem by either treating it successfully or by referring it to another expert who then treats it successfully. An expert’s record is characterized by its thickness—the decaying number of problems they diagnosed over time—and the expert’s reputation—their decaying historic success rate in solving problems. Reputation is directly payoff-relevant in that demand for the expert’s services increases in their reputation but decreases in an aggregate index of the their competitors’ reputation, perhaps the market average. The record’s thickness, on the other hand, does not directly affect demand but the inertia of the expert’s reputation. The thicker an expert’s record, the less today’s success rate matter in determining reputation.

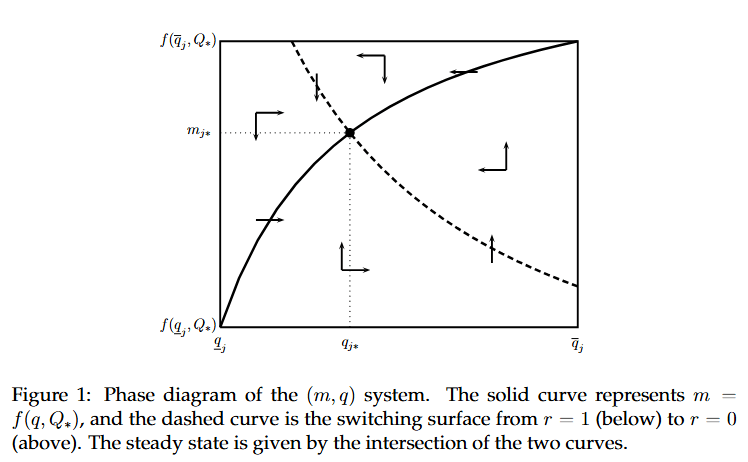

We describe experts’ referral behavior in the unique steady state Markov equilibrium of our model. Uniqueness of the steady state follows from a feedback loop induced by the laws of motion that determine the expert’s record. As an expert refers more mismatched problems, their reputation increases, and so does their demand leading to a thicker record. Then, ultimately a tipping point is reached, at which reputation becomes sufficiently inert to the current success rate. As a result, the expert ceases to refer, and, ultimately, their record’ thickness decreases. This feedback loop is illustrated in the phase diagram below: